-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

K. Shaheen, M.C. Alraies, A.H. Alraiyes, A. Ibrahim, B. Altaqi, A lung cancer masquerader, QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, Volume 108, Issue 2, February 2015, Pages 151–155, https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcs146

Close - Share Icon Share

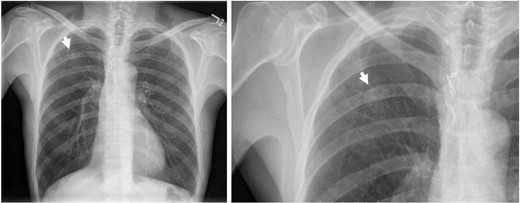

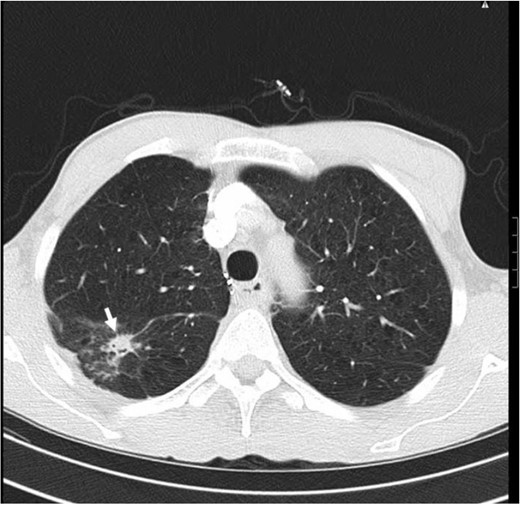

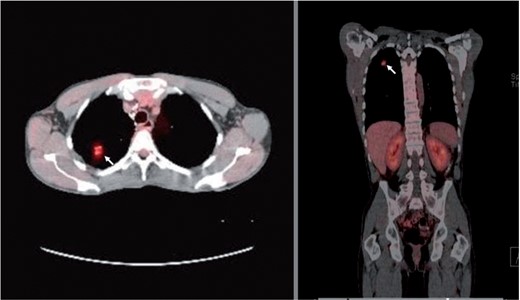

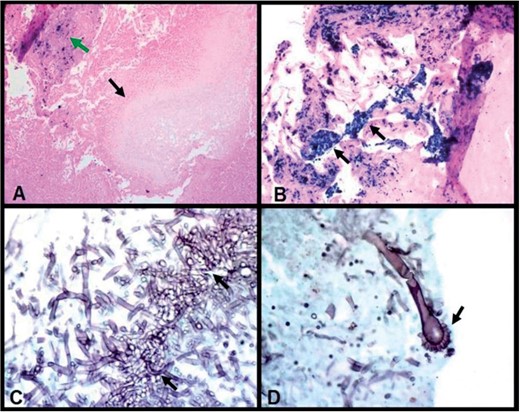

A 58-year-old man presented with 3 months history of hemoptysis. He denied having fever, night sweats, chest pain, shortness of breath, orthopnea, loss of appetite or unintentional weight loss. He had 60 pack-year history of smoking, quit 5 years ago. He did not drink alcohol and never used illicit drugs. He worked as a welder for 30 years and reported no history of sick contacts or travel abroad. His past history was remarkable for hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He had right upper lobectomy 5 years ago for suspicious pulmonary nodule in an outside facility. He was informed that his nodule was related to his occupational exposure. His medications which adequately controlled his pulmonary symptoms were inhaled tiotropium and albuterol. On physical examination, his vital signs revealed a temperature of 37.1°C, BP of 135/81 mmHg, heart rate of 85/min, respiratory rate of 16/min and O2 saturation of 97% on room air. He appeared comfortable and not in acute respiratory distress. Chest examination showed scar of previous right-sided thoracotomy, otherwise, no additional breath sounds. There was no clubbing or cyanosis. The remainder of the examination was unremarkable. Laboratory tests showed WBC 5.6 × 109/l, hemoglobin 13.0 g/dl and pletlets 180 × 109/l. INR 1.19 and PTT 25.6 s. His basic biochemical profile and urine analysis were normal. The chest radiograph (CXR) showed a 1.5 cm multiform density nodular shadow in the right upper zone (Figure 1). A computed tomographic scan (CT) showed a 1.5 cm solitary nodular shadow in the superior segment of right lower lobe with no hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy (Figure 2). The 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose and positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scan showed a focal area of increased uptake (standard uptake values—SUV—of up to 3.8) at the site of the right nodular shadow. There was no abnormal uptake in the mediastinum or outside the thorax (Figure 3). Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 70 mm/h (reference range 0–20 mm/h) and C-reactive protein (CRP) was 105 mg/l (reference range 0.0–3.0 mg/l). Sputum culture and acid fast bacilli were negative. Since it was extremely difficult to identify the nature of this nodule and to rule out malignancy, a right-sided thoracotomy with wedge resection was carried out. Patient had excellent post-operative recovery. Final histopathology revealed aspergillus fumigatus organisms present in a cavity space (Aspergilloma—fungal ball with a size of 2 mm in diameter). This was associated with surrounding chronic granulomatous inflammation, fibrosis and sheets of macrophages having cytoplasmic iron pigment suggestive of pulmonary siderosis. No malignant cells were seen (Figure 4). The diagnosis of aspergilloma complicating pulmonary siderosis was made.

Chest x-ray showing an 1.5 cm multiform density nodular shadow in the right upper zone (arrow).

CT scan of the chest, lung window, showing 1.5 cm irregular solitary nodular shadow in the upper segment of right lower lobe (arrow). There is no associated hilar or mediastinal lymph nodes enlargement.

Fused PET/CT scan of the chest. Axial (left panel) and coronal (right panel) images showing moderately increased uptake (FDG uptake with SUV of 3.8) in the right lung nodular lesion (arrows).

Wedge resection histopathology of the right lung nodule demonstrates pulmonary siderosis and aspergilloma. (A) Cavity containing pale-staining proliferating fungal hyphae (lower arrow) (fungal ball—aspergilloma, a size of 2 mm in diameter) with iron staining in adjacent fibrous scar (upper arrow) (Prussian blue iron stain, 100×). (B) Dense interstitial fibrosis containing clusters and sheets of macrophages with cytoplasmic bright blue iron pigment (arrows) (Prussian blue iron stain, 200×). (C) Medium-power photomicrograph shows clusters of acute angle branching fungal hyphae of aspergillus fumigatus (arrows) (Grocott Methenamine Silver-GMS stain, 400×). (D) High-power photomicrograph demonstrates aspergillus fumigatus conidiophore with classic fruiting head (arrow). (GMS stain, 630×).

Discussion

Pulmonary siderosis (welder’s lung) is a pneumoconiosis disease caused by chronic iron inhalation. It occurs in about 7% of arc welders. A diagnosis of pulmonary siderosis is based on the patient history of exposure to iron dust particles, radiographic findings and pathologic finding of iron oxide in macrophages within the lung.1 Clinical symptoms are usually non-specific and mainly include shortness of breath, cough and sputum production. Although it takes years of exposure for a patient to become symptomatic, rapid development of symptomatic disease within a year after exposure has been reported.2,3 A typical radiographic finding of pulmonary siderosis includes ill-defined centrilobular micronodules that are diffusely distributed in the lung.1 Despite the striking radiological and histopathological features, it has traditionally been described as a ‘benign pneumoconiosis’ because of the absence of associated symptoms, functional impairment or pulmonary fibrosis in general.1 Although several reports showed evidence of fibrosis in the lungs of welders,1 siderosis with local fibrosis described from pathology or occupying mass/nodular lesion on chest CT scans has been rarely reported.1

Here we present a case of Welder’s siderosis with local fibrosis mimicking lung cancer. Because the radiographic findings were atypical and the increased uptakes in FDG-PET scan, we conducted a thoracotomy and open wedge resection procedure to exclude the possibility of lung neoplasm and unexpectedly revealed local fibrotic lesion and iron containing macrophages due to pulmonary siderosis. The patient had no exposure to silica or asbestos which may develop interstitial fibrosis and there was no evidence of classic silicosis or asbestosis on CT scan or histological examination. So it is reasonable to suspect that the local fibrosis in this patient was a reaction to iron particles. Furthermore, this local fibrosis may have resulted in a cavitation which was complicated by aspergilloma growth.

Aspergilloma (fungus ball) is formed when aspergillus colonize and grow into a cavity. It is typically seen in patients with a preexisting lung cavity from a variety of causes, such as pulmonary tuberculosis, lung cancer (following successful treatment), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, fibrocavitary sarcoidosis and pneumoconiosis.4 Typically, radiologic finding of aspergilloma is a solid, round or oval mass with soft-tissue opacity within a lung cavity, manifesting an ‘air crescent sign’. In our case of aspergilloma, air crescent was interrupted on plain chest film and CT scan probably due to the tiny small size of aspergilloma ball and the limit of radiographic and CT resolution. To our knowledge, aspergilloma in the context of pulmonary siderosis have been rarely reported.5

Although positron emission tomography (PET) is now an important imaging tool in lung cancer, the increased uptake of 18F-FDG in benign pulmonary lesions is not uncommon. PET scan with FDG is based on the increased glucose metabolism of lung cancer cells. Increased glucose metabolism can also be seen in many inflammatory conditions and results in enhanced FDG uptake (False-positive FDG uptake) such as in bacterial pneumonia, pyogenic abscesses, aspergillosis, Cryptococcosis, Paragonimiasis and active granulomatous diseases such as tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, histoplasmosis, Wegener’s granulomatosis and other inflammatory entities.6 FDG-PET studies have also revealed increased uptake in pneumoconiosis with combined massive fibrosis and aggregates of particle-laden macrophages, a reaction that is typically seen with inert dusts such as iron, tin and barium. In these lesions the FDG uptake has been attributed to the presence of inflammatory cells activity (i.e. granulocytes and/or macrophages as well as fibroblasts).6

Management

The treatment of pulmonary siderosis is usually symptomatic. It is important to realize that this inert iron oxide could cause local fibrosis and an accurate diagnosis should be obtained. Avoidance of iron dust exposure and implementing prevention strategies in people at risk are the mainstay of therapy where prognosis is generally favorable. The patient was advised to change his job to avoid further lung impairment. In co-existing aspergilloma, watchful waiting is appropriate if it is simple and asymptomatic.7,8 Patients who are symptomatic, particularly for those with hemoptysis, surgical resection is the most appropriate intervention in order to prevent or treat potentially life-threatening hemoptysis.7,8 Antifungal therapy is appropriate for those who have progressive disease with worsening symptoms and radiographic findings especially in chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis (complex aspergilloma) or chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis and those who are unable to tolerate surgery.7 Embolization may be indicated in patients who have severe hemoptysis and are too ill to have surgery or with extensive lung involvement.9 In our patient, histopathlogy and silver staining evaluations showed no fungal invasion of adjacent lung parenchyma and no evidence of angioinvasion.

Although our patient was given vericonazole during the hospital stay, it was discontinued when discharged home given that the lesion was removed with surgical wedge resection. Post-operative hospital course was uneventful and surgery resulted in resolution of his symptoms with no recurrence of his hemoptysis over 6 months follow-up. Patient reported no recurrence of his symptoms since then.

Acknowledgements

We confirm that all of the authors participated in the preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest: None declared.